Postmodernism: The Pursuit for Amelioration

- chillsarchitecture

- Apr 12, 2014

- 5 min read

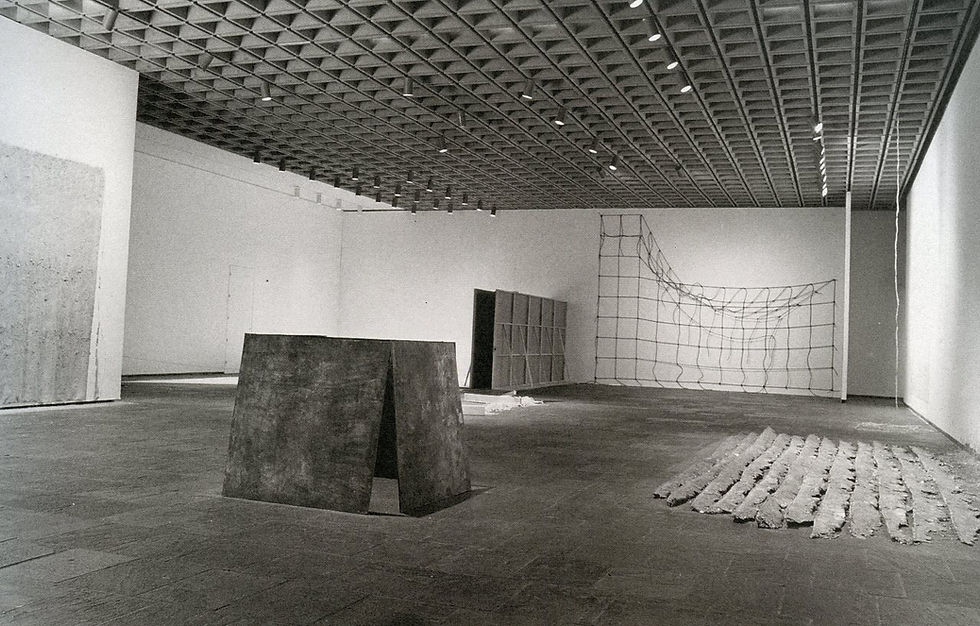

Postmodernism, a fulfilling response and counteraction to the formalities of its predecessors, most notably the avante-garde and, of course, modernism, has been the most pragmatic and beneficial, and therefore the most important artistic reconsideration and theoretical practice of the past few centuries. Rather than rising up from a singular birth, detached from historical roots, drawing inspiration solely from within, as seen in works such as Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto, postmodernism focused on what had come before, questioning history as to best prepare and equip for intellectual progress, and articulating virtue of originality. Supplying evidence of the myths of modernist conventionality in writings such as Rosalind Krauss’s reflective and insightful book of 1986, "Originality of the Avante-Garde and Other Modernist Myths", and in sculpture such as Richard Serra’s brilliant “One-Ton Prop” of 1969, modernism and the avante-garde are exposed to a light of truth and criticism so enlightening that it virtually discredited the generating power of the styles and paved way for revolutionary artistic intentions and engines of thought.

As Krauss speculates and highlights the flawed intellectual processes behind modernism, she reveals the platforms on which postmodernism rose, supporting the necessity for revolution that the movement adopted. Krauss introduces the miscalculations of the modernism movement by discrediting the definitions of “originality” and “uniqueness”, revealing their unavoidable encounters and relationship with replication and formula. Pointing out the weakness and defect of one of modernism’s most popular styles, the grid, she explains how the grid contradicted itself entirely. The modernist grid essentially built a trap of a tireless search in discovering the absolute ground zero of art. While defending its appeal in communicating “silence, exile, and cunning”, describing it as the emblem of original purity, Krauss dutifully examines its discrepancies. Modernism strived for absolute originality and artistic freedom from precedent, but the grid was inherently a trap for repetition and “extremely restrictive in the actual exercise of freedom.” “The grid can only be repeated….The (modernist) artist engages in repeated acts of self-imitation.”

With careful consideration of Krauss’s publication endorsing postmodernism, I felt a certain obligation to apply her theories to the works of Richard Serra. In his lead antimony sculpture One Ton Prop, Serra embraces the revolutionary ideas that halted the progression of modernist movements and provided excellent territory for which to launch the new, retorting exercise of postmodernism. In this sculpture, Serra carefully applies an interpretive grid structure in the formulation of his process, considering its purity and ability to “figure forth the material ground of an object, inscribing and depicting the object.” He operated on this idea that the grid enables the rise of an organized sculptural matter. The identical, geometric calculations of the plates in his sculpture offer dialogue between Serra’s postmodernist position and the modernist’s grid-purity aphorisms. It reveals the character of Postmodernism as a response to what was deemed admirable and/or erroneous in modernism. Serra’s practice of sculpture and manipulation of this grid layout, however, reveals the freedom that postmodernists strived for in rebellion of the tight confinements of grid purity.

Krauss’s opening in the Originality of the Avante-Garde reveals her postmodernist views on replication and duplicates, exposing the truth behind what is and should not be considered original works of art. Krauss interrogates society as being a “culture that clings to originals”, senselessly and unreasonably. She embarks on the discoveries of artist’s relationship to works of duplication and copies, and defends the artists, explaining that there is truly not even such an existence of an original work of art. In studying the reality of original, in our perspective, from the perspective of postmodernism, “its objecthood, its quiddity, is only a fiction; that every signifier is itself the transparent signified of an already-given decision to carve it out as the vehicle of a sign”. She explains, “…from this perspective there is no opacity, but only a transparency that opens onto a dizzying fall into a bottomless system of reduplication.” This exposure further strengthened the postmodernist movement and its fulfillment through response to the errors of modernism.

We can see in Serra’s sculptural practice, an unavoidable presence of reduplication. He exhibits this element very obvious in One Ton Prop through his use of a multiplied, identical object, the plate, displayed four times. His construction of the sculpture, a delicate balance between interdependencies that dance between structural stability and wavering, innovatively summons a discussion on the interdependencies of originality and formulaic repetition as argued by postmodernism.

Serra’s trademark aesthetic simplicity in this piece, a characteristic sought after in the minimalist movement of postmodernism, and found most distinctively in his early works, he seems to be exposing yet another flaw in modernism, one that is investigated by Krauss as the prevarication of impressionism. She unmasks it as a beautiful illusion of spontaneity of an original, singular experience that embodies the deceptive empirical array of modernism, noting it as “the most fakable of signifieds.” Its entire process was a scam of the gesture technique, and in exposing its honest process, completely contradicted modernist ideals. From this fraud blossomed the responsive, minimalist movement that Serra used as yet another tool in One Ton Prop sculpture’s discourse on the postmodernist approach to modernism.

Finally, along with her incrimination of the grid, Krauss criticized modernists’ close-minded approach to artistic precedent, arguing the consideration of historical endeavors and intellectualism to be essential to the progression of new mindedness and enlightenment. The avante-garde stood on the platform of self-origin. However safe this mindset is from contamination, it is ultimately unsuccessful. She refers to William Gilpin’s theories on singularity and the picturesque, and explains “priorness and repetition of pictures is necessary to the singularity of the picturesque, because for the beholder, singularity depends on being recognized as such, made possible only by a prior example.” As the entire character of postmodernism acts as a sort of rebellion to the ethics of modernism, we can see in Serra’s works the employment of precedent research as a primary resource for the creation of his identity as an artist. We recognize his works to be vital in the progression of the art of this era because of the emblems it voices in contrasting response to the previous examples of modernism found in art at the time.

In art, the advance and development of the intellectual minds of an era depend entirely on the ability of that generation to question the validity of its context. Postmodernism is the most vital example we have in recent centuries to practice this concept of progression, and has thus paved the way to the artistic expressions, ideals, and freedoms found in current conditions of art. Through the articulate and contemporary studies of Krauss and more importantly, the action carried out by artists such as Richard Serra in response to modernism and myths of the avante-garde, change is generated in motion towards the product of preferment that propels progression in artistic intellect and practice. Postmodernism stands as an example to modern society and art culture to continuously inquire on the efficacy and legitimacy of modern context in order to proceed practice in the most fulfilled and valid intellectual position possible.

Written for my course “Art Since 1960”, Postmodernism: The Pursuit for Amelioration was an exploration into the validity of postmodernism and how it changed the art world for the better. Although my research was not focused specifically on architectural results of postmodernism, what I learned through the process of this paper helped me to better understand how and why architecture is influenced by revolutionary movements in the art world.

Sources:

Krauss, Rosalind E. Originality of the Avante-Garde and Other Modernist Myths. MIT Press, 1986. Print. 1-19.

Zurbrugg, Nicholas. Critical Vices: The Myths of Postmodern Theory. British Library Catologuing in Publication Data. Amsterdam, 2000. 51-52.

Comments